45 Years Rooted: 1

“For there are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt, of examining what our ideas really mean (feel like) on Sunday morning at 7 AM, after brunch, during wild love, making war, giving birth; while we suffer the old longings, battle the old warnings and fears of being silent and impotent and alone, while tasting our new possibilities and strengths.”

I’ve been fascinated by history recently. Maybe because it’s just concrete enough to grasp in these times where we all need something to grasp onto. Maybe it’s something about the meaningless of it all: that we’ve all thought everything there is to be thought. It takes some of the pressure off, especially for those of us existing in this rat race of the nonprofit industrial complex. Everything has to be the most groundbreaking, the most innovative, the most new. Everything has to be genre defining- the next big framework! The next big movement wide concept! The next thing to hit critical mass!

I started looking into AARW’s archives a year and a half ago now at the urge of my former colleague Arpita Joyce, who was working with me to build out AARW’s narrative and cultural strategy. This was before Trump was elected a second time, and before this barrage of nonsensical executive orders and techno authoritarianism. This was before the urgency became even more urgent, and the meanings of the nonprofit rat race started to make less and less sense. As I’ve continued to look through our archives, I’ve been able to relive some of that scrappy, revolutionary spirit from when AARW was just a little collective that could.

This is not to discount the importance of nonprofits, of course. This is certainly not to discount the importance of funding or the very real conditions of repression and defunding that we’re organizing in. It’s imperfect, after all. AARW has this 45+ year history of constantly shifting, constantly reevaluating what it means to be in this very particular Asian American organizing space in Boston.

One of the most helpful reports I came across in the archives was titled “Building a People’s Movement: Grassroots Organizing in the Boston Asian Community”, which seems to have been written for a class held in November 1985 called “Intellectuals and Social Change” by Professors Louis Kampf and Noam Chomsky, and submitted by Robert Chien-chuan Chu and Hei Wei Chan.

The report outlines the basic struggles and material conditions of the Asian community in Boston in the 80s, and some of the defining organizational moments of several of the leading Asian American movement organizations at the time, including AARW. What shocked me was the windiness of the report’s section on AARW. Where other organizations had straightforward routes from, for example, organizing tenants in a single building, to expanding to neighborhood wide campaigns, to growing to corporate or city government pressure campaigns, AARW’s origins zigzagged from organizing coffeehouses (open mics for Asian American artists) and Chinese folk singing groups to organizing those very same people that came for community into anti-Asian violence campaign committees like Asians for Justice and the Committee to Support Long Guang Huang.

Shirley Mark, one of the founding members of AARW, was interviewed by a past intern Jelina Liu, and she described what it felt like when AARW first started.

“The AARW at that time was… very activist. You didn’t need to schedule a meeting, if you will. We just had things going on all the time, and people would drop in, they would show up and say ‘what can I do?’. They would just show up and hang out, and we were involved in so many things.”

When asked about one of her fondest memories at AARW, Shirley describes the feeling of the coffeehouses, one of AARW’s earliest consistent programming.

“One of my fondest memories of the AARW is that, when I first started getting involved when I was still a college student, they had what were called coffeehouses. It was like an open mic, you’d call it an open mic now. So we had these coffee houses… It was a chance for AAPI artists and performers to just come together and have fun. And so people would go up and sing folk songs, they would read poetry that they wrote, they would do little skits, just a range of different cultural and artistic performances which were really amazing for community building. And I think a lot of us developed our deep friendships, lifelong friends through meeting people in those casual settings. It wasn’t through like an explicit issue that we worked on together. I mean sometimes it was, but oftentimes it was just people coming together as individuals because that was an open and safe space for people to be, and we would just have a potluck or something.”

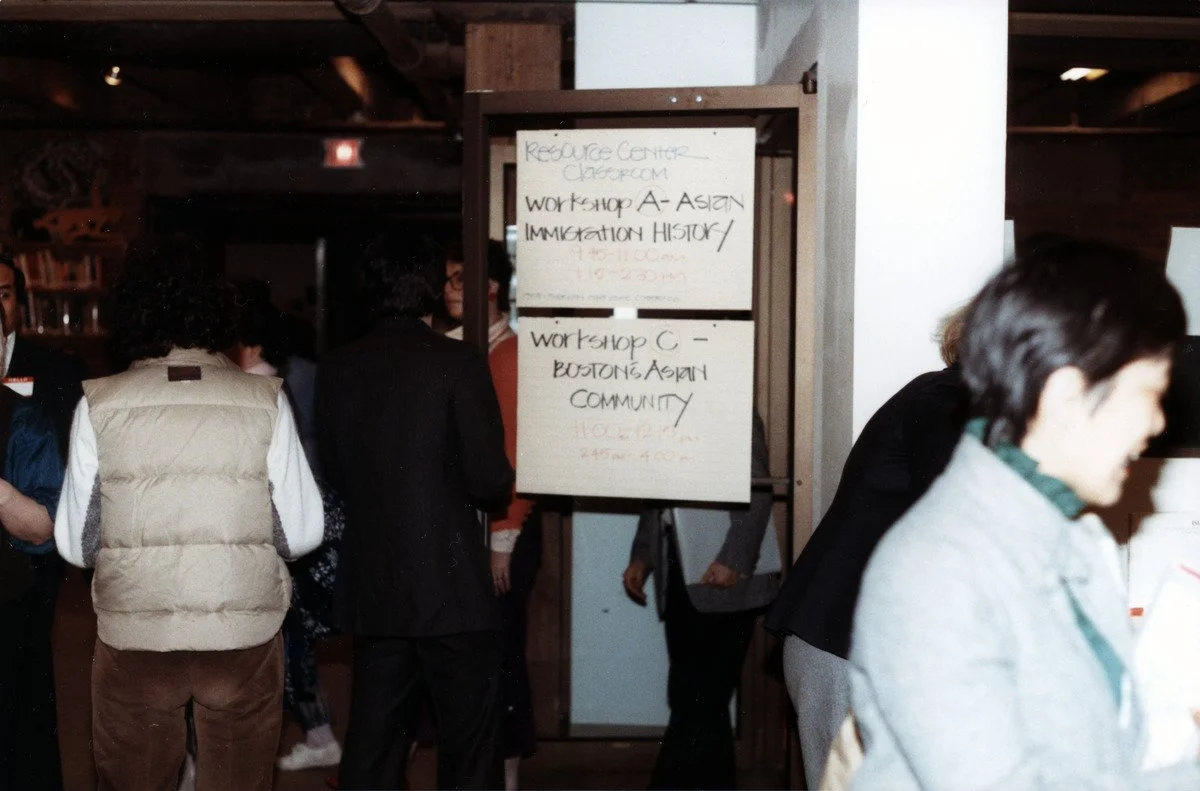

This all happened at a time when AARW had little to no paid staff. Shirley came on as staff a little bit later, but for the first few years of AARW, it was a period of “shoestring budgets, intense excitement, and a lot of sheer hard work” (according to the Building a People’s Movement report). If you read through the history of AARW’s early years outlined in this report, it spans the gamut of what was happening both nationally and locally at the time. It was responding to the wave of Asians appearing in cinema, and their racist portrayals. It was responding to the lack of any understanding of “Asian American” in the academic sense, and training teachers and support students to establish Asian American studies. It was being the first organization to bring many different Asian ethnicities together under one roof to share and celebrate their cultures, doing things like having a Pilpino dance troupe perform at a Lunar New Years festival, which had never been done before in Boston’s Chinatown. It was supporting Chinese Progressive Association (CPA), who was right down the hall from AARW’s first office on 27 Beach St, in their anti-gentrification organizing.

All this, of course, was not at all what I expected to read when I looked into AARW’s early history. I had always heard that AARW was an arts and culture organization, which then shifted to organizing, but I think that narrative is too simple. The report claims that what made AARW different from all the other organizations at the time was its relentless commitment to its own evaluation and its pan-Asian origins. It was its commitment to the idea of Asian American consciousness, which I admit I didn’t understand the historical significance of until I started looking into the political milieu of that particular time.

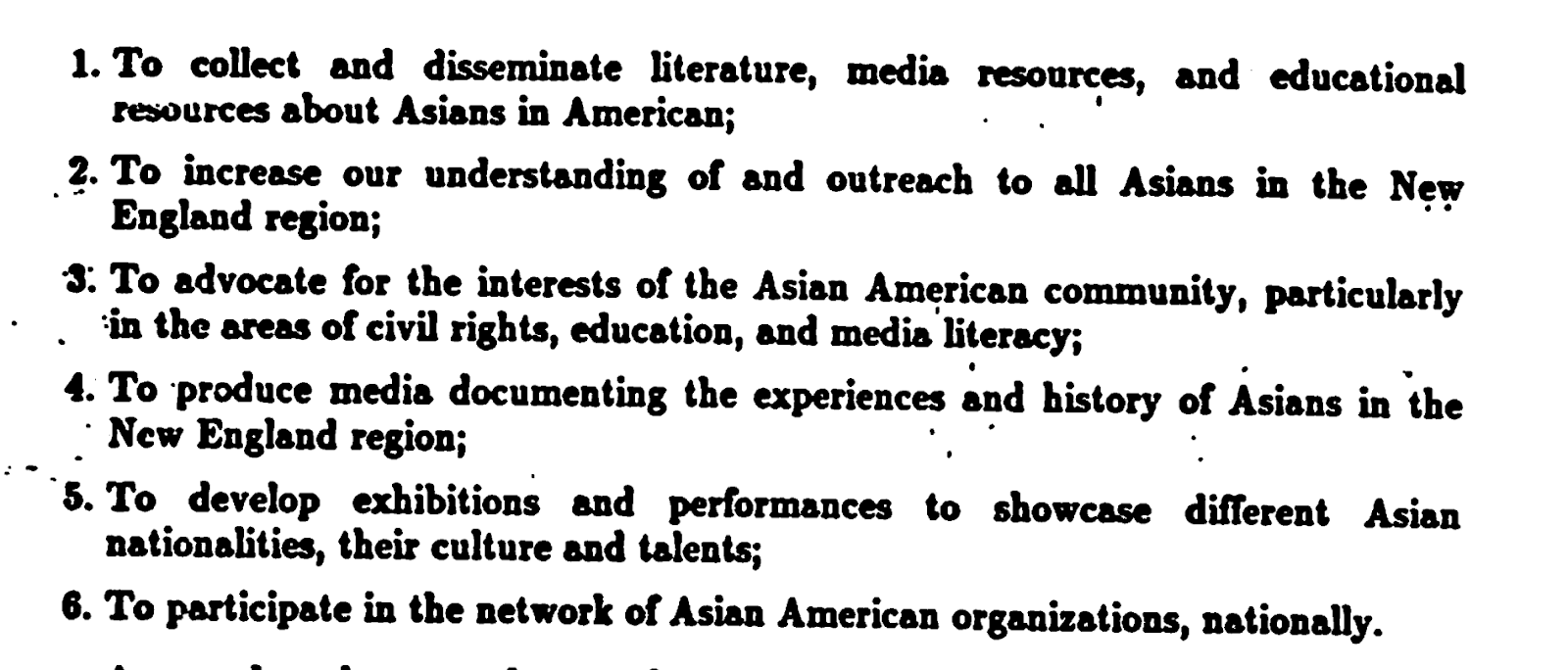

From AARW’s September 1984 retreat, this was our mission statement:

This mission statement, much like our current one, is incredibly vast. Sometimes that vastness can feel overwhelming. It can feel meaningless. It can feel both too little and too much for the funders that want a snappy elevator pitch of what we do, or the strategic communications imperative of the shorter, simpler, and more repetitive, the better.

At the same time however, it feels absolutely right. As the Director of Narrative Strategy at AARW, I am often saddled with the task of making clear what we do to people who have either never heard of us, or only interacted with us in one area of our work. To explain that we do deportation defense work, organize for housing justice, have a strong arts and culture history, and build youth leadership can feel unwieldy, and at times too complex. But I think there is something defining about that scrappy little collective that still exists in our mission, vision, and ethos. I don’t want to lose that essence of what it means to be grassroots in the midst of all the real panic and material ways in which our communities and organizations are suffering in this time of heightened danger.

Going through the archives has been a balm to some of the worst bouts of paralysis that I’ve felt since the beginning of this new year and all the chaos it has brought. It’s a reminder that the physical danger our communities are in has, unfortunately, happened before, and we’ve dealt with it. That we not only organized against violence and repression, but that we also had time to learn, and sing, and write. That we always kept the imperative of broad base building across different Asian communities at our forefront, and that base building didn’t always look like a serious campaign meeting or heavy hearted protest.

I’ll be going through some of the highlights from my archival research over the next month to highlight the ways in which AARW has both grown and stayed firmly rooted over the past 45 years. I’ll particularly be focusing on one of our major campaigns during the late 80s, the campaign to support Long Guang Huang, which ties together the intersections of crimmigration, housing justice, and pan-Asian base building. I hope to bring some type of illumination from the past, or at least provide something interesting to think about, or another case study to learn from.

At our 45th anniversary event, we’ll have archival materials from this phase in AARW’s history and more, which we encourage you to join us in person to interact with! All info can be found at aarw.org/45yearsrooted.

Dianara Rivera (she/her) is a queer, mixed race Pilipina Puerto Rican woman who is committed to supporting Asian American communities in narrative organizing. She currently serves as the Director of Communications and Narrative Strategy at AARW, building out storytelling projects that build power and advance our campaign goals. Dianara credits the fight for collective liberation as the catalyst for learning how to heal herself and others. She holds bachelors degrees in Ethnic Studies and Creative Nonfiction Writing from Brown University. Outside of AARW, she also organizes with the Pilipino community.