45 Years Rooted: 2

I decided to focus on the case of Long Guang Huang because the archives made it seem like a big deal. It’s a huge part of our archival material, with multiple boxes full of photographs, typewritten notes, press releases, reports, and so much more. (I even read about the existence of a short film AARW produced about the Long Guang Huang campaign, which I couldn’t find any records of despite how badly I wanted to!) As I dove deeper into this campaign and learned about the political milieu that accompanied its development, I saw so many parallels to the ways we’ve narratively and politically defined ourselves, and how we’ve always explained why we do the work we do.

Just like the intertwining of arts, organizing, identity formation, and the pressures of material conditions that created the early community building spaces of AARW, the Long Guang Huang campaign came to be at the perfect pinpoint of multiple political crises coming to a head. The Long Guang Huang campaign was a perfect example of adapting to the crises of the moment, while also combatting and redefining the narratives that defined our identity formation as Asian Americans.

The Run Up

A picture of Long Guang Huang, from the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA) archives

Long Guang Huang was a Chinese immigrant living in Boston’s Chinatown in 1985. He was brutalized by plainclothes police officer Francis G. Kelly Jr. in Chinatown’s then-called “Combat Zone”. and charged with assault and battery of a policeman, despite being assaulted in broad daylight. Around this time of the late 1980s, there had been a rising tide of “anti-Asian violence”, a term and concept that the Asian American community was able to find unity around. (We’ll talk more about that term and the utility of using it later.) The term “Asian American” was still newly formed, and the Asian American movement was gaining traction. University of California Berkeley graduate students Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka had just named their student group the “Asian American Political Alliance” in 1968, and the Third World Liberation Front had successfully won Ethnic Studies through massive student strikes in 1969. The American War in Southeast Asia, commonly known as the Vietnam War, had ended in 1975, and Boston’s Southeast Asian population had swelled due to refugees being resettled into the area.

At the same time, the film industry was just starting to take off. AARW had screened Hito Hata, the first Asian American produced feature length (silent) film. AARW’s Media Group was formed out of the success of that showing, and it went on to mobilize community members to protest screenings of racist movies. One of the most vivid examples of the violent portrayals of Asians in the movies at that time was the release of the movie Rambo in 1985. Sylvester Stallone played a Vietnam war veteran who returns to Vietnam in search of missing Prisoners of War, and murders many Vietnamese soldiers that try to stop him. This film, which was essential to establishing Stallone as a bona fide American movie star, justified violence against Vietnamese Americans and Asian Americans. Its effects were seen both locally and across the country, with a catastrophic rise in anti-Asian violence that year.

I like to call these early days of media activism the beginnings of AARW’s narrative organizing, which I continue today in my own role as Director of Narrative Strategy. I’m the first to say that representation is the bare minimum of what narrative strategy should strive to achieve. What is interesting to me though is how closely the organizing around protesting violent portrayals of Asians in media was tied to organizing around violence against Asian Americans in real communities. Given that media was a burgeoning field at that time too, it’s not lost on me how the fight against harmful narratives was one that had outsized influence on how Asian communities were treated in real life.

From AARW’s 1984 newsletter

Most significant to the conversation about Long Guang Huang’s campaign, however, was the national uprising over the murder of Vincent Chin in 1983. Vincent Chin, a Chinese American, was murdered by two unemployed auto workers who mistook him for a Japanese American, and blamed him for their inability to get work. AARW, along with many other organizations around the country, organized to support him. The Vincent Chin Ad Hoc Committee was formed by many of the same people in AARW’s Media Group. True to the spirit of a grassroots organization, the Vincent Chin Ad Hoc Committee kept evolving as the material conditions changed. With the rising amount of violence, especially against Southeast Asian refugees resettling into Dorchester and workers in Chinatown, the Vincent Chin Ad Hoc Committee remade itself into Asians for Justice. Two years later, in 1985, Asians for Justice pivoted to meet the moment again and reformed as part of the Committee to Support Long Guang Huang.

(image from AARW’s To Live in Peace report on anti-Asian violence)

The Committee to Support Long Guang Huang distributes information at a table the August Moon Festival in Chinatown, taken from the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA) archives

Things happened quickly after the assault on Long Guang Huang. Two days after the assault, community members distributed a bilingual flyer inviting the community to a meeting. The next day, 300 Chinatown residents packed the local public school auditorium, leaving that auditorium with a list of eight demands and a newly formed Committee to Support Long Guang Huang, which AARW’s Asians for Justice folded into. The campaign to support Long Guang Huang would develop into a six month long affair, spanning several community groups working in coalition, intense media advocacy, and scrupulous community engagement. It would encompass demands that ranged from radical to reformist, and end in Long Guang Huang winning his case and winning “justice”, whatever that meant at the time.

The “Combat Zone” and anti-displacement organizing

Picture of a man at a rally to Support Long Guang Huang, from the CPA archives

The Long Guang Huang campaign was an early example of our anti-displacement framework in action. One of my favorite things about looking through old photos of rallies is to see the slogans and calls to action that community members put on signs. I love this sign that includes the call for “community control”. While AARW’s anti-displacement framework may seem random for some, I think this sign shows that we have always organized from the point of view of preventing the displacement of our people, whether that’s through gentrification, over policing, or violence.

The fervor to support Long Guang Huang was a long time coming. Because of Chinatown’s prime location in the middle of the city, it was becoming coveted land. Luxury developers were pushing in, and both the Boston Redevelopment Authority and Tufts Medical Center were grabbing up land, reducing the amount of land in Chinatown by half. At the same time, the city government designated a strip of inexpensive land on Washington Street between Boylston Street and Kneeland Street the official red light district. This was done without the input or consent of the community. Boston police officers frequently patrolled this area due to the stigma against sex work and the immigrant community, which led to many instances of police brutality. The brutalization of Long Guang Huang happened in this stretch of the “Combat Zone”.

One of the more radical demands from the Committee to Support Long Guang Huang was the demand for the immediate development of plans to eliminate the Combat Zone in Chinatown, and gain community control of the land in Chinatown. While an anti-displacement framework was not included in the narrative framework for the Long Guang Huang campaign, I think it was the beginnings of bridging the two issues of housing and crimmigration that AARW continues to do today.

Long Guang Huang was one of the Chinatown residents that suffered from the lack of community control over the area. Chinatown residents were being run out by rising rent prices, and police officers were feeling audacious enough to brutalize a Chinatown resident in plain daylight, not even wearing uniforms that identified themselves. On top of that, the police department tried to press charges on Long Guang Huang for assaulting a police officer, when in reality he was the one that assaulted. All of these factors were direct results of the underfunding, over policing, and increasing non livability of the Chinatown area that the city government was directly contributing to.

This was also one of the rallying points that allowed the Long Guang Huang campaign to move beyond just a Chinatown issue to an Asian, and even wider multiracial, campaign. The gentrification of communities of color is far from new. Just as the mayor tried to change Dudley station into a galleria for the “benefit of the Black community”, the mayor tried to eliminate the Combat Zone by bringing in luxury developments like Lafayette place to “benefit the Chinatown community”. The answer to supporting communities of color was never bringing in luxury buildings to gentrify the community, but allowing the community to decide how their land will be used themselves.

Community organizing, and the narrative stakes

The Long Guang Huang campaign was an early example of insisting that communities won’t be pushed out, and an early attempt at tackling the issue of the criminalization of immigrants and refugees. For all it solidifies the way we move today, it also has many lessons on how we shouldn’t. It was a campaign on the brink of a narrative battle for humanity and dignity, and one that missed the mark when it came to imagining past the carceral systems we have in place.

The Committee to Support Long Guang Huang crafted demands that addressed two key issue areas that continue to affect the Asian American community, no matter what time period: housing justice and the intertwining of the criminal legal system and the immigration system (also known as the crimmigration system). It also began to move towards addressing the ramifications of the criminalization of immigrants, but was ultimately reactionary in that it only worked to reform the police force, rather than imagine a different system entirely.

As is obvious by the demands, the Committee was heavily focused on interacting with city officials and the police department. Their main demands were to secure an investigation into Officer Kelly’s violent misconduct and secure compensation for Long Guang Huang’s injuries. One reason why there is so much documentation around this campaign is because it is one of the first instances of mass community organizing that went beyond just Chinatown organizing. Police accountability and anti-Asian violence was an issue and narrative that the broader Asian American community found compelling to rally around. It’s important to think about why it was so easy for the issue of “anti-Asian violence” to become a rallying point for the burgeoning Asian American movement at that time. The narrative of combating violence did help to counter the dominant narrative at the time of Asians as quiet and docile, but it also focused on the harms done to Asian Americans, instead of the strength and imagination of the Asian American community. The narrative push for Asian American inclusion within the state institutions of the police and city government helped to secure short term material protections for the community, but also set the battleground for community safety firmly in the realm of what already exists, instead of allowing room for the building of something different and better.

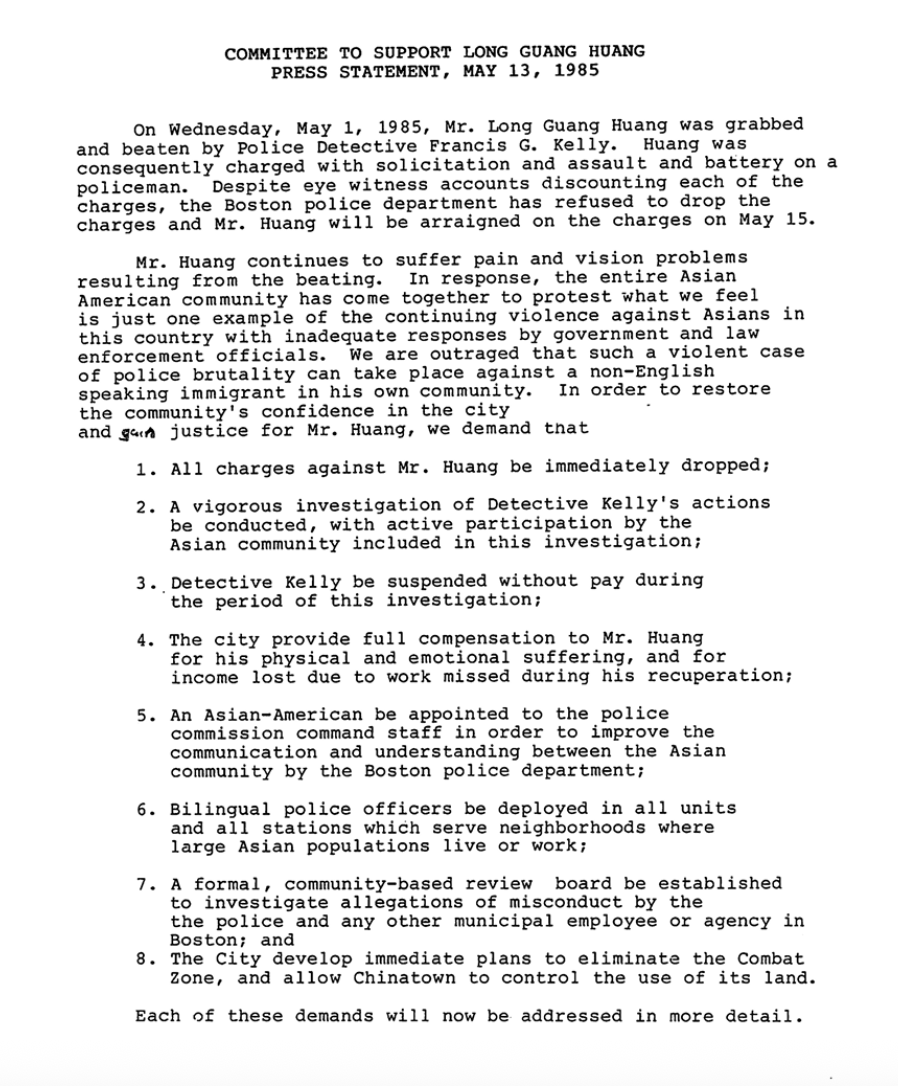

the demands from the Committee to Support Long Guang Huang

The campaign for justice for Long Guang Huang was ultimately a campaign about what it meant to be safe as Asian Americans at that time. It was ultimately about how organizing is a form of community safety, not just for Asians, but for all people of color. It’s admirable how community organizing turned devastating violence into something as hopeful as unity. It’s impressive how the rallying cry to support Long Guang Huang reached far beyond Chinatown and even the city of Boston, serving as another example of why the identity of “Asian American” has always been intrinsically tied with the liberation of other ethnic and racial communities, even those that we don’t know we have much in common with on the surface.

We can all learn from the mass mobilization the Long Guang Huang case inspired. We can learn from its narrative successes and failures. What is perhaps most comforting to me, however, is just how long we’ve been doing this. Just how long we’ve been testing and reiterating the most effective ways to build power.

I’ll leave us not with a picture of a mass mobilization, a campaign strategy meeting, or a speaker at a rally. I’ll leave us with pictures from my favorite set of photos from the Long Guang Huang archives, photos showing several community members serving food at a sign-making meeting. This, to me, is the essence of community organizing. Not the protests and the slogans. The quiet moments where people bonded, did something to help their neighbors, and maybe learned something about what it means to be part of a community.

Dianara Rivera (she/her) is a queer, mixed race Pilipina Puerto Rican woman who is committed to supporting Asian American communities in narrative organizing. She currently serves as the Director of Communications and Narrative Strategy at AARW, building out storytelling projects that build power and advance our campaign goals. Dianara credits the fight for collective liberation as the catalyst for learning how to heal herself and others. She holds bachelors degrees in Ethnic Studies and Creative Nonfiction Writing from Brown University. Outside of AARW, she also organizes with the Pilipino community.